The ethno-photographer (Part I)

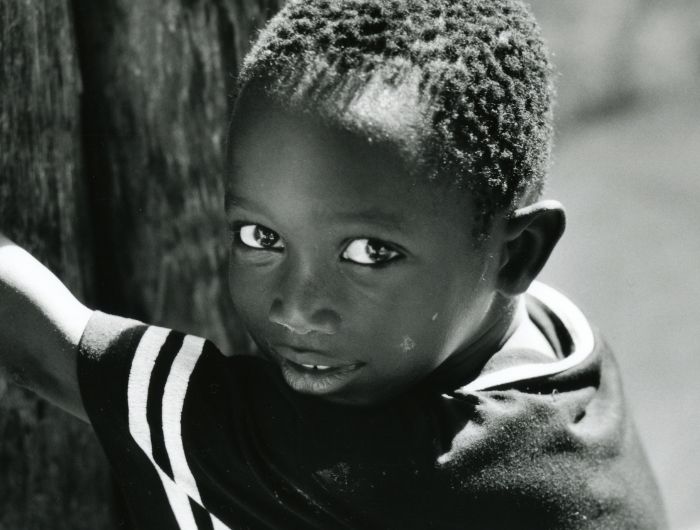

This series of two articles discusses the practice and use of photography as part of anthropological research report on poverty in Senegal (Dakar) and Ethiopia (Dire Dawa). The analysis focuses on the scientific value of the information provided by photos as an ethnographic document. The research field of the anthropologist constitutes a complex environment. Moreover, when the topic of research requires observation of socially marginalized populations living in difficult contexts of accessibility, as well physicals as socials, the study of poverty according to an anthropological approach constitutes a highly sensitive research field. In order to deal with the obstacles that are typical to such research, it is necessary to develop an adequate methodology which allows the observation of people’s living conditions. The methodology developed here presents the role of the Ethno-photographer, who provides access to scientific observation.

Justification of the approach

Anthropology analyzes the manifestations of social life. Observing details, the anthropological approach allows the comprehension of conscious, unconscious and symbolic events which constitute social life. The object of anthropological studies is life. In 1950, Marcel Mauss[i] underlined this fundamental and single characteristic of anthropology.

As an interpretation of cultural phenomena, anthropology seizes at the same time collective phenomena and individual expressions which are the manifestations of social life. Consequently, the specificity of an anthropological research lies in its capacity to describe observations of different cultures without any a priori opinion. Ethnography, as a method of investigation in anthropological research, refers to the collection, classification and transcription of information collected during in the research field. It reports the observation of events and constitutes the memory of testimony. Assuming ethnography is the transcription of raw data, one should consider the fact that any ethnography is part of the observation process and thus constitutes a primarily cultural interpretation of the observer. Indeed, is the eye that sees and the ear that listens represent “culture”. A “virgin interpretation” does not exist because it relies on cultural background, therefore thought and ordered, otherwise social built. Thus, human observation is being in the incapacity to perceive a meaningless space. In his book titled Exercices d’ethnologie, Robert Jaulin[ii] highlights these problems by showing that the observation faculty is linked to the cultural interpretation process.

This characteristic of intellect clearly reflects the limit of human observation when used to report socials phenomena. This seems to be in opposition to any scientific approach. Consequently, any ethnographic method must consider this restrictive aspect. In fact, the mere presence of the researcher near the population he would like to study does not guarantee the success of the ethnographic study. The scientific value of the analysis depends on the precision of the observations reported, as well as continual confrontation of information collected and interpretative assumptions. Any anthropological observation should aspire to self-criticism and requires doubt. The first challenge of the research field is not physical but rather intellectual because it requires neutralizing all a priori perspectives. Anthropological research forces the anthropologist to complete a self reflection process in order to eradicate any exoticism and any ethnocentrism. He must transform an experiment of personal life, his research field, into scientific work. The anthropologist is requested to struggle daily against ethnocentrism!

The ethnographic methodology presented in this article is based on the practice of photography. This method does not lack difficulties, some of which are directly related to the scientific value of the information collected through visual support such as the photo itself. By constituting an extension of the human eye, the photographic picture is a direct result of a cultural process. Thus, it is legitimate to assume that photography, by its own divisions of the scene observed, can contribute to building specific objects in opposition with reality. This danger, although relevant to all aids allowing the anthropological data-gathering, reminds us that a picture provides a subjective portrayal of reality because it is subjected to the visual and psychological interpretation of the observer (photographer). The need “to frame” a particular event constitutes a first division of the reality observed, based on the choice of the observer. Nevertheless, the careful selection of the subjects photographed and the particular photographic techniques, as well as the scientific analysis allows overcoming the limitations associated with the photographic picture within the context of an ethnographic study. Thus, this method serves as a data acquisition tool that allows collecting information with scientific value that may exceed that collected by other tools, particularly writing.

With this in mind, let us consider the practice of photography in the context of a scientific approach that views society in its globality. This approach claims that society is not made up of an linear continuation of individuals but form an indivisible totality. This totality includes behaviours, structures and values which characterise the society that the ethnography proposes to reveal via photos. Let us first present the characteristics of conducting research with marginalized populations of the capital of Senegal and the Dire Dawa town in Ethiopia, before presenting the suggested methodology.

Poor districts of Dakar and Dire Dawa: a harsh environment for anthropological research

At a first impression, Dakar seems to be an unpleasant city. Its size, the macrocephaly of the urbanization and intense traffic create a busy atmosphere. In addition, the harassing and daily requests of the bana bana[iii] and street hawkers of any kind provide a constant source of agitation. Moreover, the study of the perception of poverty requires tying strong relations with populations that are difficult to reach due to their economic and social conditions. These elements make the observation fragile. Poor populations occupy certain districts described as unhealthy and dangerous, where high crime rate is prevalent and where the majority of residents live under very poor conditions. For a few years, a renewal of violence in certain poor districts during religious holiday periods such as the tabaski[iv], has made it difficult to carry out ethnographic research in these places.

For these reasons and others, conducting anthropological research in the poor districts of the capital is difficult. Particularly since Senegal is an “ethnologized” country, i.e., the population is frequently the subject of various studies financed by local authorities, international organizations and institutions. This represents an additional difficulty with an investigation of families, insofar as the population has certain “experience” with research. Thus, people may be fast to reply a question in a biased way or worse, adopt an attitude that is intended to satisfy the interrogations of the researcher. In addition, the rise of mass tourism since the 1980s has strongly influenced the lifestyle of the population and contributed to establishing certain ideas regarding the western way of life. This may have contributes to the construction of an a priori notion associated with the researcher. These characteristics of the Senegalese capital are additional challenges for conducting anthropological research in situ.

Tourists specifically and westerners in general, are often judged as being uninterested in the culture of the country and insensitive to the populations living conditions. Although this interpretation reflects a certain reality of a majority of tourists, it strongly harms the anthropologist. Consequently, anthropologists are indirect victims of mass tourism and popular beliefs. They too are harassed, like any other foreigner, by street hawkers and curious people which try to make profit from the westerners. In addition, some people may try to sell their contribution to the study and provide false information attempting to satisfy the anthropologist. There is no doubt, despite all his efforts, the anthropologist is still seen as a foreigner in the eyes of the local community.

Dire Dawa (Ethiopia) also poses many difficulties when it comes to carrying out research on poverty. First, political tension in this area close to Ogaden, a region bordering with Somalia, is intense and constant. Ethiopian military troops are deployed in order to ensure the control of its border with Somalia and to limit incursions of armed groups into the area. This area is characterized by residual stresses of conflicts and sporadic confrontations with various armed groups. This element poses an additional difficulty in conducting anthropological research in Dire Dawa. Indeed, authorities are cautious and suspicious with foreigners and even more so with people who are devoted to research on a sensitive topic such as poverty and displacement of populations at the regional level. Conducting research on poverty forces the researcher to answer questions regarding the reasons for his presence in the area and regarding the goals of his work. Also, the risk of bomb attack should not be overlooked. In June 2002, Dire Dawa was subjected to bomb attacks by the Oromo Liberation Forces, which however, did not claim any casualties. More recently, a few weeks after my field work was completed, in May 2008, a murder attack struck the capital Addis-Ababa.

The flow of refugees coming from Ogaden and Somalia creates problems for the Ethiopian authorities. This flow is an important source for an increase of population settled in Dire Dawa. The majority of newcomers settle in the peripheral districts, which contributes to the development of an “anarchistic” occupation of urban space. In addition, the high concentration of the population is accompanied by an increased instability of living conditions and a lack of security in the poor districts and suburbs. Problems relating to refugees remain taboo for local administrations. The latter is reluctant to recognize needs and is unwilling to address the unstable social and economic living conditions of these populations.

Although these difficulties are attenuated over time, the anthropologist is constantly observed by the local population becoming the study subject of his own subjects. This is characteristic of any ethnographic research field and it calls the anthropologist to create a specific methodology which takes into account the characteristics of the research environment as well as his own personality. As for me, I chose to appear as photographer. This choice had two goals. First, it was used in order to limit personal interrogations and, second, to provide a legitimate reason for my presence in the area while creating a role for myself within the community. Indeed, presenting oneself as an anthropologist is often difficult to explain: the work and research goals are never easy to comprehend. Choosing to appear as a photographer helps avoiding ambiguities related to my presence in the area and allows me to be an actor while enabling me to preserve a certain freedom for conducting my field work. For me, this role occurs in the community towards the construction of my character, a photographer and an anthropologist at the same time, that I named the Ethno-photographer.

Creating the Ethno-photographer: the focal point of the anthropological approach.

Anthropological research based on the practice of photography presupposes an initial phase in which one must create the first contact with the population studied as a photographer. This requires establishing oneself as a photographer whose purpose is to document the social life of the district. Using an easily identifiable character, like a photographer, seems to have proven reliable by other anthropologists such as Laurence Wylie[v] who in September 1950, settled in Peyrane[vi] in Vaucluse, and used photography to approach the local population.

Field work requires the building a network of relationships. This is a condition necessary in order to have access to information. With that, the anthropologist must become an active observer by establishing dialogue in order to reach the information he is looking for. Though it may not be problem-free, the choice to appear as a photographer creates a local role which allows participating in the community’s activities. The behaviour and choices which follow from this approach are easily understandable to the target population and my social and cultural status are clear as someone who is an anthropologist and a photographer at the same time: the Ethno-photographer.

Establishing relationships based on trust seems to be a prerequisite for the practice of photography in particular, and when conducting anthropological research in general. In Senegal, among the poor population, appearance is a decisive criterion in creating social relations and it also determines the qualitative aspect of the relation. Appearance refers both to the physical and dress appearance and to gestural and linguistic expression. The element of appearance has a dominant role in the process of identification and construction of relationships between individuals. The anthropologist should, as much as possible, be free to choose his relations. He meets some individuals who may be interesting subjects for his research and others who are less so. The anthropologist must also provide a certain amount of information about himself. The extent to which a participant will open up to the researcher and the quality of the information he will provide depend on establishing a trusting relationship between the two.

The anthropologist and the interviewee do not speak the same language and in the case of my research, the interviewee is not from the same social and cultural environment. As for linguistic differences, difficulties of interpretation are important to pay attention to. In spite of using the French language, words meaning are not identical, sometimes not even similar, cultural referents are divergent from one society to another and also within the same society, from one social status to another. Partly in order to limit the risks of an erroneous interpretation of information, photography is used together with audio recording of the speech and note taking whenever possible. These aids, far from being contradictory, are in fact complementary. Beyond words, the picture makes possible the description of a symbolic idea contained in the discourse and the physical body, while speech and writing replace picture in the initial context of the subject.

The second part of this article will discuss the photographic technique and the scientific content in photos in the context of anthropological research.

From François-Xavier de Perthuis de Laillevault. Article published in the review Le Panoptique, 2011, 13th of February.

[i] Mauss, 1950 : 285

[ii] Jaulin, 1999 : 43

[iii] Street sellers

[iv] The al aide kabire (tabaski) is celebrated two months and approximately ten days after the Ramadan. It is one of the most significant religious events in West Africa.

[v] Wylie, 1968 : 18

[vi] Such as the author mentions it, the name “Peyrane” does not correspond to the real name of the village, this one having been voluntarily dissimulated in the work of the author.